With no horizon.

Miguel Zugaza.

On the Painting of Gonzalo Chillida

To the reader. In what follows I am posing a series of images which, in my opinion, are pertinent to accompany the complete itinerary that this publication proposes with regard to the painter Gonzalo Chillida. The mere reproduction of these works, most of them quite familiar, alongside those by the painter from San Sebastián, will prove, in my judgment, to be extraordinarily eloquent for understanding where his artistic course is set. With them I include some brief comments about shipwrecks, the loss of the horizon, and the poverty of our contemporary gaze.

l

Amongst the more or less apocalyptic readings of our contemporary era, that of the shipwreck is without a doubt one of the most persuasive, in part because it is propounded by artists themselves. The first omen of the tragic outcome was painted stormily by the German Caspar David Friedrich in his Monk by the Sea (Fig. 1), the first image I will evoke here. It was painted in 1808, during the Napoleonic domination of Europe, a period of great insecurity in which our contemporary sensibility was suddenly awakened. We may concluded that the subject of this painting is the horizon as the threshold of despair. It speaks of the contemporary man as standing on the tightrope marking the separation between heaven and earth, his gaze upon that disturbing strip of the wild Northern sea. The German painter’s man is a monk, a militant of salvation, who faces the unfathomable uncertainty of providence.

1. Caspar David Friedrich.

Monk by the Sea, 1808.

Oil on canvas. 110×171.5 cm.

Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Nationalgalerie.

Some years ago, Bob Rosenblum unravelled the complicity between Friedrich’s existential vision with the more abstract one of the work of another Northern painter: Mark Rothko (Fig. 2). It was a relief to realise what our monk could see in the forbidding landscape. Three strips of superimposed colour, three luminous strata that shimmer on the surface of the canvas. We are bold enough to sing, like a Psalm, “Abstraction is salvation!”. The threshold no longer torments us, the horizon again reveals itself as a promise, a way of transcendence in life.

Untitled (Black on Gray), 1969-1970.

Acrylic on canvas. 203,3×175,5 cm.

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York.

The Spaniard Goya, a contemporary of Friedrich, also perceived the sinister shadow that falls on our contemporary experience, In his celebrated Perro semihundido / Drowning Dog (Fig. 3), painted a few years after Monk by the Sea, surrounded by other frightful scenes on the wall of his home, Quinta del Sordo, Goya narrowed even further the space of our existence, hiding the image of horror from us. The entire painting becomes an immense glaze, like the sea reflecting a storm-wracked sky.

3. Francisco de Goya.

Perro semihundido / Drowning Dog, 1820-21.

Mural in oil transferred to canvas. 131.5×79.3 cm.

Museo del Prado, Madrid.

But let us not put the cart before the horse.

Contemporary art was not built upon the line of horizon in the landscape, but upon another horizon, on the edge of a table, an imperfect edge like those painted by the Spaniard Luis Meléndez. The most traditional still life was the genre in which the revolution of contemporary art was waged, or, in other words, where art was relieved of its obligation to merely imitate nature. This was the case of Cubism, breaking the bonds of geometric illusionism. The painting unfolds itself like the waves of a roiling sea, shattering the flatness of classical perspective.

Space is narrowed extraordinarily and in a way different from the Gothic bas-reliefs that served as inspiration to Van der Weyden for his Descent from the cross (Fig. 4), another great painting of folds. The creases of Cubism are different, apparently disordered, chaotic, and definitely lacking a horizon. On Weyden’s panel the figures swirl around the fundamental gravity of the action of the descent of Christ’s body from the Cross just as later on the castaways would descend from the meagre space of the remains of Gericault’s Medusa (Fig. 5). Shipwrecks in painting do not end here. Manet takes up the theme in his series on the naval combat between the Kearsarge and the Alabama, reminding us that before Cubism the undulating folds of the sea had already wreaked havoc on our modern consciousness. And they are not as shipwrecked as those objects that tremblingly swirl around in the centre of the works by the Bolognese Giorgio Morandi.

4. Rogier Van der Weyden.

Descent from the Cross, c. 1432

Oil on panel. 220×262 cm.

Museo del Prado, Madrid.

5. Théodore Géricault.

The Raft of the Medusa, 1819.

Oil on canvas. 491×716 cm.

Musée du Louvre, París.

ll

The fact is that before –long before—our particular contemporary tribulations, admittedly rather desperate, painting had shown us something about its own limits. Before the advent of Cubism –long before– we witnessed another great “avant-garde” revolution, that of realism, led by Caravaggio (Fig. 6), whose international diffusion had a particularly stormy impact on Spanish artistic culture. That movement, whose follower soon became legion, sought to rebuild a credibility that had been lost, a new promise of salvation. It was then that a new light shone out from the darkness, a theatrical, dramatic light. Reality was not now reproduced, but rather revealed, like Narcissus’ reflected countenance, in the camera obscura of painting. Light and shade, chiaro and oscuro.

6. Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio.

Narcissus, 1598-99.

Oil on canvas. 110×92 cm.

Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Antica, Palazzo Barberini, Rome.

In Spain, the Carthusian painter Sánchez Cotán made us genuflect before the sinister frame of a window showing a cardoon and three carrots (Fig. 7). Times of prayer and watchfulness. Meanwhile, Zurbarán filled humble ceramic pieces with water. (The fasting of our gaze began but, in spite of the hardship, what a succulent promise for a castaway).

7. Juan Sánchez Cotán.

Bodegón del cardo / Still life, 1600.

Oil on canvas. 68×89 cm.

Museo del Prado, Madrid.

In some fashion, it was with the triumph of naturalism that the poverty of our gaze and of painting itself was established. Even before the horizon was erased. Salvation was never closer to us, to our senses. You can take it, or leave it. Like beggars, hungry for sensations, we devour it with our eyes.

One of the images that best attests to our destitution is that of La Santa Faz / Holy Face, insistently depicted by Francisco Zurbarán, among others. Let us take for instance the painting that now hangs in Stockholm (Fig. 8). What we see is nothing more than one small linen cloth on top of another. A cloth folded upon itself hanging with the carelessness of a sheet hung to dry in the sun. The image of the Saviour is blurred and feeble, like a shadow. We know that the industrious Spanish painter made these works in the last years of his life for his private devotions, doubtless to produce in the darkness of a small chapel the emotion of divine revelation. As if it were a photographic laboratory, in a dark room the image appears timidly on the emulsified surface of the photographic paper, mixed up in the folds of the water, and later hung with pegs on a line.

8. Francisco de Zurbarán.

La Santa Faz / Holy Face, c. 1630.

Oil on canvas. 70×51,5 cm.

Modernamusset, Stockholm.

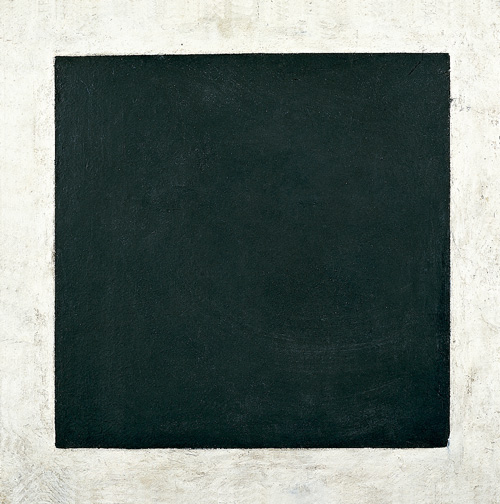

When we regard Zurbarán’s Holy Face we are moved by its simplicity. A white canvas painted as a trompe l’oeil on another white canvas. It is a prelude to the finale, presaging the triumph of the “minimal”. The truth is that, like the castaway, we will settle for very little, wetting our lips with a sip of fresh water. Zurbarán, like Malevich (Fig. 9), will later betray the poverty of our gaze, the little that remains for us to see. Later, perhaps, a light will appear at the end of the tunnel, or at least silence. Painters of icons, of images of salvation.

9. Casimir Malevich.

Black Square, c. 1930.

Oil on canvas. 53.5×53.5 cm.

Hermitage, Leningrad.

Before crashing against the cliff of Cubism, the impoverished gaze of contemporary man resists the notion of the end, and before becoming entirely self-absorbed it indulges itself by butting insistently against that other cliff that is the threshold of Monet’s Rouen Cathedral (Fig. 10), naturally before even Monet himself became self-absorbed in the contemplation of the mirror-like surface of the Giverny ponds. The painting ends up as a litany. The insistent prayer of a monk facing the sea. We cannot stop looking, toward the light, toward the landscape itself even if it be only the folds that sketch the meanderings of the water on the golden surface of the sand, now without a horizon. Deep, and with no horizon (Fig. 11)

10. Claude Monet.

Rouen Cathedral, 1894.

Oil on canvas. 107×73 cm.

Musée d’Orsay, Paris.

11. Gonzalo Chillida

Sands, 1987.

Oil on canvas. 120×120 cm.

Museo of Bellas Artes, Bilbao.

Monograph Gonzalo Chillida. Pintura/Paintings. Editing Alicia Chillida. Tf. Editores, Madrid 2006.